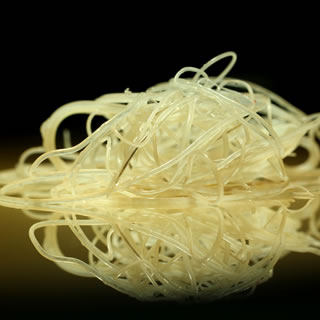

Heartworm disease is a serious and potentially fatal disease in pets in the United States and many other parts of the world. It is caused by foot-long worms (heartworms) that live in the heart, lungs and associated blood vessels of affected pets, causing severe lung disease, heart failure and damage to other organs in the body. Heartworm disease affects dogs, cats and ferrets, but heartworms also live in other mammal species, including wolves, coyotes, foxes, sea lions and—in rare instances—humans. Because wild species such as foxes and coyotes live in proximity to many urban areas, they are considered important carriers of the disease.

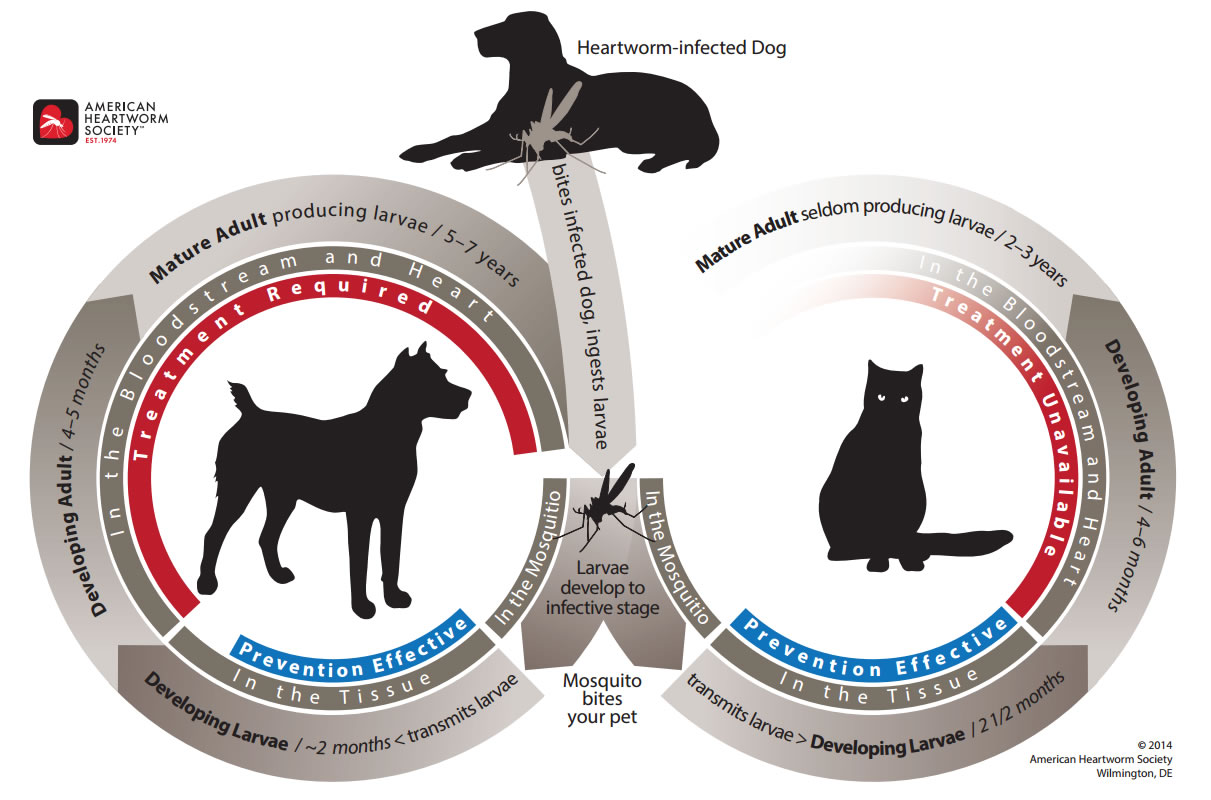

Dogs. The dog is a natural host for heartworms, which means that heartworms that live inside the dog mature into adults, mate and produce offspring. If untreated, their numbers can increase, and dogs have been known to harbor several hundred worms in their bodies. Heartworm disease causes lasting damage to the heart, lungs and arteries, and can affect the dog’s health and quality of life long after the parasites are gone. For this reason, heartworm prevention for dogs is by far the best option, and treatment—when needed—should be administered as early in the course of the disease as possible. Learn more about heartworm medicine for dogs.

Cats. Heartworm disease in cats is very different from heartworm disease in dogs. The cat is an atypical host for heartworms, and most worms in cats do not survive to the adult stage. Cats with adult heartworms typically have just one to three worms, and many cats affected by heartworms have no adult worms. While this means heartworm disease often goes undiagnosed in cats, it’s important to understand that even immature worms cause real damage in the form of a condition known as heartworm associated respiratory disease (HARD). Moreover, the medication used to treat heartworm infections in dogs cannot be used in cats, so prevention is the only means of protecting cats from the effects of heartworm disease.

Ferrets. Heartworm disease in ferrets is caused by the same parasite that causes heartworm infection in dogs and cats. The disease in ferrets is an odd mix of the disease that we see in dogs and cats. Like dogs, ferrets are extremely susceptible to infection and can have larger numbers of worms than cats, but like cats, a low number of worms, perhaps just one, can cause devastating disease due to the small size of the heart. Heartworm disease is often more difficult to diagnose in ferrets and there is no approved treatment. Prevention is imperative for both indoor and outdoor ferrets.

The mosquito plays an essential role in the heartworm life cycle. Adult female heartworms living in an infected dog, fox, coyote, or wolf produce microscopic baby worms called microfilaria that circulate in the bloodstream. When a mosquito bites and takes a blood meal from an infected animal, it picks up these baby worms, which develop and mature into “infective stage” larvae over a period of 10 to 14 days. Then, when the infected mosquito bites another dog, cat, or susceptible wild animal, the infective larvae are deposited onto the surface of the animal's skin and enter the new host through the mosquito’s bite wound. Once inside a new host, it takes approximately 6 months for the larvae to develop into sexually mature adult heartworms. Once mature, heartworms can live for 5 to 7 years in dogs and up to 2 or 3 years in cats. Because of the longevity of these worms, each mosquito season can lead to an increasing number of worms in an infected pet.

In the early stages of the disease, many dogs show few symptoms or no symptoms at all. The longer the infection persists, the more likely symptoms will develop. Active dogs, dogs heavily infected with heartworms, or those with other health problems often show pronounced clinical signs.

Signs of heartworm disease may include a mild persistent cough, reluctance to exercise, fatigue after moderate activity, decreased appetite, and weight loss. As heartworm disease progresses, pets may develop heart failure and the appearance of a swollen belly due to excess fluid in the abdomen. Dogs with large numbers of heartworms can develop a sudden blockages of blood flow within the heart leading to a life-threatening form of cardiovascular collapse. This is called caval syndrome, and is marked by a sudden onset of labored breathing, pale gums, and dark bloody or coffee-colored urine. Without prompt surgical removal of the heartworm blockage, few dogs survive.

Signs of heartworm disease in cats can be very subtle or very dramatic. Symptoms may include coughing, asthma-like attacks, periodic vomiting, lack of appetite, or weight loss. Occasionally an affected cat may have difficulty walking, experience fainting or seizures, or suffer from fluid accumulation in the abdomen. Unfortunately, the first sign in some cases is sudden collapse of the cat, or sudden death.

The signs of heartworm disease in ferrets are similar to those in dogs, but they develop more rapidly because the ferret’s heart is quite small. While dogs may not show symptoms until they have many worms infecting their hearts, lungs and blood vessels, just one worm can cause serious respiratory distress in a ferret. Symptoms of this distress include • Lethargy (i.e., fatigue, tiredness) • Open-mouth and/or rapid breathing • Pale blue or muddy gum color • Coughing

Many factors must be considered, even if heartworms do not seem to be a problem in your local area. Your community may have a greater incidence of heartworm disease than you realize—or you may unknowingly travel with your pet to an area where heartworms are more common. Heartworm disease is also spreading to new regions of the country each year. Stray and neglected dogs and certain wildlife such as coyotes, wolves, and foxes can be carriers of heartworms. Mosquitoes blown great distances by the wind and the relocation of infected pets to previously uninfected areas also contribute to the spread of heartworm disease (this happened following Hurricane Katrina when 250,000 pets, many of them infected with heartworms, were “adopted” and shipped throughout the country).

The fact is that heartworm disease has been diagnosed in all 50 states, and risk factors are impossible to predict. Multiple variables, from climate variations to the presence of wildlife carriers, cause rates of infections to vary dramatically from year to year—even within communities. And because infected mosquitoes can come inside, both outdoor and indoor pets are at risk.

For that reason, the American Heartworm Society recommends that you “think 12:” (1) get your pet tested every 12 months for heartworm and (2) give your pet heartworm preventive 12 months a year.

Heartworm disease is a serious, progressive disease. The earlier it is detected, the better the chances the pet will recover. There are few, if any, early signs of disease when a dog, cat or ferret is infected with heartworms, so detecting their presence with a heartworm test administered by a veterinarian is important. The test requires just a small blood sample from your pet, and it works by detecting the presence of heartworm proteins. Some veterinarians process heartworm tests right in their hospitals while others send the samples to a diagnostic laboratory. In either case, results are obtained quickly. If your pet tests positive, further tests may be ordered.

Testing procedures and timing differ somewhat between dogs, cats and ferrets.

Dogs. All dogs should be tested annually for heartworm infection, and this can usually be done during a routine visit for preventive care. Following are guidelines on testing and timing:

Annual testing is necessary, even when dogs are on heartworm prevention year-round, to ensure that the prevention program is working. Heartworm medications are highly effective, but dogs can still become infected. If you miss just one dose of a monthly medication—or give it late—it can leave your dog unprotected. Even if you give the medication as recommended, your dog may spit out or vomit a heartworm pill—or rub off a topical medication. Heartworm preventives are highly effective, but not 100 percent effective. If you don’t get your dog test, you won’t know your dog needs treatment.

Cats. Heartworm infection in cats is harder to detect than in dogs, because cats are much less likely than dogs to have adult heartworms. The preferred method for screening cats includes the use of both an antigen and an antibody test (the “antibody” test detects exposure to heartworm larvae). Your veterinarian may also use x-rays or ultrasound to look for heartworm infection. Cats should be tested before being put on prevention and re-tested as the veterinarian deems appropriate to document continued exposure and risk. Because there is no approved treatment for heartworm infection in cats, prevention is critical.

Ferrets. Diagnosis of heartworm disease in ferrets can be more problematic. Your veterinarian may recommend both antigen testing and diagnostic imaging such as echocardiography to demonstrate the presence of worm in the heart.

No one wants to hear that their dog has heartworm, but the good news is that most infected dogs can be successfully treated. The goal is to first stabilize your dog if he is showing signs of disease, then kill all adult and immature worms while keeping the side effects of treatment to a minimum.

Here's what you should expect if your dog tests positive:

Like dogs, cats can be infected with heartworms. There are differences, however, in the nature of the disease and how it is diagnosed and managed. Because a cat is not an ideal host for heartworms, some infections resolve on their own, although these infections can leave cats with respiratory system damage. Heartworms in the circulatory system also affect the cat’s immune system and cause symptoms such as coughing, wheezing and difficulty breathing. Heartworms in cats may even migrate to other parts of the body, such as the brain, eye and spinal cord. Severe complications such as blood clots in the lungs and lung inflammation can result when the adult worms die in the cat’s body.

Here’s what to expect if your cat tests positive for heartworm:

Ferrets are extremely susceptible to heartworms.There are differences, however, in the nature of the disease and how it is diagnosed and managed. Ferrets are extremely susceptible to heartworms. Heartworms in the circulatory system also affect the ferret’s immune system and cause symptoms such as coughing, wheezing and difficulty breathing, even sudden death. Ferrets may also demonstrate fluid in the lungs, decreased appetite and weight loss, paralysis of the hind legs, or enlarged abdomen. Bilirubinuria (dark colored urine) is common in ferrets with heartworm disease.

Here’s what to expect if your ferret tests positive for heartworm:

Yes. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labeling on heartworm preventives states that the medication is to be used by or on the order of a licensed veterinarian. This means heartworm preventives must be purchased from your veterinarian or with a prescription through a pet pharmacy Prior to prescribing a heartworm preventive, the veterinarian typically performs a heartworm test to make sure your pet doesn't already have adult heartworms, as giving preventives can lead to rare but possibly severe reactions that could be harmful or even fatal. It is not necessary to test very young puppies or kittens prior to starting preventives since it takes approximately 6 months for heartworms to develop to adulthood. If the heartworm testing is negative, prevention medication is prescribed.

Whether the preventive you choose is given as a pill, a spot-on topical medication or as an injection, all approved heartworm medications work by eliminating the immature (larval) stages of the heartworm parasite. This includes the infective heartworm larvae deposited by the mosquito as well as the following larval stage that develops inside the animal. Unfortunately, in as little as 51 days, heartworm larvae can molt into a juvenile/immature adult stage, which cannot be effectively eliminated by preventives. Because heartworms must be eliminated before they reach this adult stage, it is extremely important that heartworm preventives be administered strictly on schedule (monthly for oral and topical products and every 6 months or 12 months for the injectable). Administering prevention late can allow immature larvae to molt into the adult stage, which is poorly prevented.

Yes, a number of heartworm preventives used today also are effective against certain intestinal parasites. Depending on the product, these may include hookworms, roundworms, whipworms and tapeworms. Some products are even effective in treating external parasites such as fleas, ticks, ear mites, and the mite that causes scabies. However, it is important to realize that no single product will eliminate all species of internal and external parasites, and you should consult your veterinarian to determine the best product for your pet.

The risk of puppies and kittens getting heartworm disease is equal to that of adult pets. The American Heartworm Society recommends that puppies and kittens be started on a heartworm preventive as early as the product label allows, and no later than 8 weeks of age. Ferrets are started on a preventive when they weigh at least two pounds.

The dosage of a heartworm medication is based on body weight, not age. Puppies and kittens grow rapidly in their first months of life, and the rate of growth—especially in dogs—varies widely from one breed to another. That means a young animal can gain enough weight to bump it from one dosage range to the next within a matter of weeks. Ask your veterinarian for advice about anticipating when a dosage change will be needed. If your pet is on a monthly preventive, you may want to buy just one or two doses at a time if a dosage change is anticipated (note that there is a sustained-release injectable preventive available for dogs 6 months of age or older). Also make sure to bring your pet in for every scheduled well-puppy or well-kitten exam, so that you stay on top of all health issues, including heartworm protection. Confirm that you are giving the right heartworm preventive dosage by having your pet weighed at every visit.

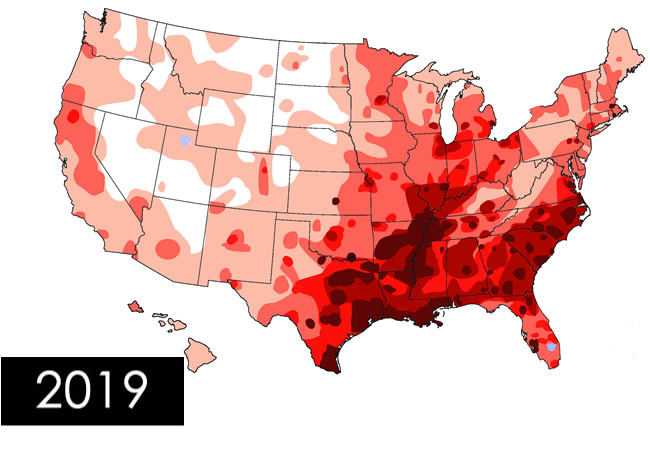

Heartworms have been found in all 50 states, although certain areas have a higher risk of heartworm than others. Some very high-risk areas include large regions, such as near the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, and along river tributaries. Most states have "hot spots" where the heartworm infection rate is very high compared with other areas in the same state. Factors affecting the level of risk of heartworm infection include the climate (temperature, humidity), the species of mosquitoes in the area, presence of mosquito breeding areas, and presence of animal “reservoirs” (such as infected dogs, foxes or coyotes).

For a variety of reasons, even in regions of the country where winters are cold, the American Heartworm Society is now recommending a year-round prevention program. Dogs have been diagnosed with heartworms in almost every county in Minnesota, and there are differences in the duration of the mosquito season from the north of the state and the south of the state. Mosquito species are constantly changing and adapting to cold climates and some species successfully overwinter indoors as well. Year-round prevention is the safest, and is recommended. Remember too that many of these products are de-worming your pet for intestinal parasites that can pose serious health risks for humans.

There are different climates in Arizona, including micro-climates such as irrigated fields, backyard ponds, and man-made golf courses, which affect the severity and duration of the mosquito season. We also know that areas can have heartworm infection in wild species such as coyotes, and these infected wild animals can be a source of infection to your dog or cat as well. Despite the fact that heartworm disease may not be diagnosed as often in Arizona as in some other states, it is definitely present. In fact, heartworm disease has been found in nearly every county in the state.

The American Heartworm Society recommends year-round prevention, even in states like Arizona. And remember, if your dog or cat travels out of state with you or to another part of Arizona where mosquitoes are common, they may be at higher risk of exposure.

No. At this time, there is not a commercially available vaccine for the prevention of heartworm disease in dogs or cats. However, research scientists are looking at this possibility. Right now, heartworm disease can only be prevented through the regular and appropriate use of preventive medications, which are prescribed by your veterinarian. These medications are available as a once-a-month chewable, a once-a-month topical, and either a once or twice-a-year injection. You should determine the best option for your pet by talking with your veterinarian. Many of the medications have the added benefit of preventing other parasites as well.

Only heartworm prevention products that are tested and proven effective by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) should be used.

Heartworm disease is very complex and can affect many vital organs, including the heart, lungs, kidneys, and liver. As a result, the outcome of infection varies greatly from patient to patient. The adult worms cause inflammation of the blood vessels and can block blood flow leading to pulmonary thrombosis (clots in the lungs) and heart failure. Remember, heartworms are “foot-long” parasites and the damage they cause can be severe. Heartworm disease can also lead to liver or kidney failure. Dogs that are exposed to a large number of infective larvae at once are at great risk of sudden death due to massive numbers of developing larvae bombarding the vascular system. Other animals may live for a long time with only a few adult heartworms and show no clinical signs unless faced with an environmental change, such as an extreme increase in temperature, or another significant health problem.

The age of the dog is just one factor affecting the success of heartworm treatment. When making a diagnosis and administering treatment, veterinarians consider the dog’s overall health and the severity of his symptoms, as well as the results of X-rays and laboratory test results. Older dogs with long-term heartworm infections may have damage to their lungs, hearts, livers, and kidneys that can complicate heartworm treatment. To ensure the best chance of success, it is vital to follow your veterinarian’s instructions carefully. This includes severely restricting the dog’s activity, as exercise during the treatment period is the leading cause of complications.

Yes, it is recommended in the American Heartworm Society's Guidelines to do so. This should be done under the direct supervision of a veterinarian because dogs with microfilaria (baby worms in the blood that the mosquito picks up when feeding) could possibly have a reaction to the preventive. And while this is an extra-label use of heartworm preventives, it is appropriate under the supervision of a veterinarian. However, it is important that your veterinarian assesses the severity of the disease and chooses the proper preventive accordingly. By starting the prevention program you are ensuring that your dog will not get a new heartworm infection while being treated for the existing heartworm disease. Furthermore, you are helping to keep your dog from being a source of heartworm larvae (microfilaria) for mosquitoes to pick up and eventually infect other dogs. This approach makes the treatment of the existing infection more effective.

Your veterinarian is recommending what is best. Only one drug, which is called melarsomine, is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of heartworm infection in dogs; this drug should be administered by injection in the veterinary hospital. Although there are some risks associated with this medication’s use, most adult worms die quickly and can be eliminated within 1 to 3 months. Cage rest and drastically restricted exercise during this period can decrease the chances of complications from treatment.

Along with melarsomine, the heartworm treatment protocol recommended by the American Heartworm Society includes several other medications that help improve the chances of treatment success and reduce the incidence of side effects. This includes administering a heartworm preventive medication to an infected dog for 2 months prior to melarsomine treatment. Long-term, continuous use of heartworm preventives alone to treat heartworm infections, however, is not recommended as an alternative to melarsomine, because it is well documented that additional damage to the heart and lungs occurs the longer adult heartworms are present.

After treating a dog with melarsomine injections, adult worms may continue to die for more than a month following this treatment. Heartworm antigen testing is the most reliable method of confirming that all of the adult heartworms have been eliminated. Although many dogs are antigen-negative 16 weeks after treatment, it can take longer for the antigen to be completely cleared from some dogs. Additionally, even though melarsomine is highly effective, a single course of treatment may not completely clear all dogs of infection (the American Heartworm Society protocol calls for three separate injections of melarsomine. Consequently, in most cases, a dog that is still antigen positive at 4 months should be rechecked 2 to 3 months later before determining whether there are still adult heartworms remaining, and a second treatment course may be required.

Just like dogs and cats, ferrets can become infected with heartworms, and are at risk even if they are indoor pets. The signs of heartworm disease in ferrets are similar to those in dogs, but they develop more rapidly because the ferret’s heart is quite small. While dogs may not show symptoms until they have many worms infecting their hearts, lungs, and blood vessels, just one worm can cause serious respiratory distress in a ferret. Symptoms of this distress include coughing, fatigue, open-mouth and/or rapid breathing, and pale blue or muddy gum color. Preventing heartworm disease is much less expensive and much safer than treating it, just as it is for other pets, and your veterinarian can prescribe heartworm medication approved for use in ferrets. The American Heartworm Society recommends year-round prevention for ferrets as well as regular checkups with a veterinarian to ensure they stay healthy and heartworm-free.

As with all drugs or pharmaceutical products, heartworm preventives should be used before the expiration date on the package, because it is impossible to predict if it will be effective or safe. The expiration date is established by a series of tests mandated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to provide assurance that the product is effective and has undergone no significant deterioration.

You need to consult your veterinarian, and immediately re-start your dog on monthly preventive—then retest your dog 6 months later. The reason for re-testing is that heartworms must be approximately 7 months old before the infection can be diagnosed.